Day 42

Aug 3, 2017 · 1162 words

Yesterday I performed a regression using decision trees because it’s the most straightforward sklearn estimator that support multiple outputs. It turns out the use case for them is pretty similar to that of artificial neural networks.

First thing to address is decision trees vs random forests. Random forests are an ensemble of decision trees so they create a better, more generalized model (note that in yesterday’s examples the decision tree model looked like a better fit, but the random forest had a much better score overall). Decision trees alone tend to overfit.

Next is random forest (RF) vs artificial neural networks (ANN). It’s crazy how perfect some of the research out there is. I did a brief search hoping to learn more about the differences between ANNs and decision trees / random forests and came across this research paper that not only compares them, but does it in the context of forecasting building energy consumption. Too perfect.

Here’s some differences that are highlighted in the paper:

RF have fewer hyperparameters you need to worry about, and just using the default values gives really good results. ANNs are more ambiguous with their parameters, and it can be unclear how many hidden layer neurons to include (although they do mention a starting point in the article as $n+1$ hidden neurons for $n$ output nodes).

ANN is much slower to train than RF (yesterday’s use of RF was already really slow).

RF can make predictions even when some input values are missing. On the other hand ANN tends to produce more accurate predictions than RF. Nonetheless, both estimators proved to be fairly accurate.

Another report

Here is another report from MIT that compares some forecasting algorithms. It found RF to perform better than ANN. What I like about this paper is that the authors actually explain the entire prediction process in detail so it is clear what the inputs and outputs are.

They train their model every night, and every hour they use the recent model to predict the following 12 hours of data. If I understand this correctly, that means their forecast changes throughout the day as newer predictions override old ones. I was under the assumption that once values were forecasted they would remain unchanged. The benefit of this is that your forecast will adapt to unpredictable situations making it a better indicator of what is to come.

On the other hand, if the forecast is update too frequently then there is no accountability; the predicted values are subject to change at any time. In some cases a dynamic prediction makes sense (like weather forecasts). But since we are trying to make an accountable model of power usage it would be better to avoid changing the prediction (at least, avoid changing it very often) so that the user has a chance to see the dissonance between predictions and reality.

Another idea: update the forecast throughout the day, but save the old forecast. That way the user can both see an accurate model of the future and see how consistent their prediction is throughout the day.

Which one to pick?

I’m liking the sound of random forests at the moment. It may not perform as well as ANN in many situtations, but it still can do a great job and it sounds like it is much less resource intensive.

Brainstorming a prediction flow

There a a lot of ways the prediction process can be organized. Some things to consider:

- How often to train the model?

- How often to run predictions?

- If there is prediction overlap, how is it resolved?

- How much to predict? (output size)

- How much to predict off of? (input size)

- How far ahead to predict?

Regarding the last point, so far I’ve only been predicting value(s) that immediately follow my input(s). It would probably make more sense to predict farther ahead, both so that your predictions are actually useful and so that you don’t run out of forecasted values during the time when the process needs to relearn the model / make new predictions.

I don’t see a lot of value in overlapping predictions. I think it would be reasonable to predict either a full day of data or 24 hours of data at some point in advance. For instance, predicting an hour of data a day in advance. Or predicting a day of data 2 days or a week in advance. A shorter gap between prediction/actual would likely make a more accurate prediction. A longer gap (or a longer prediction) means farther predictions. A longer predictions means slower calculations. In the realtime anomaly detection report, the model predicts 1 day of data a week in advance based on the previous 4 weeks of data.

I’ll have to try a few different methods and find a reasonable compromise between accuracy and performance.

Code

For the sake of consistency between Pandas and non-Pandas list structures, I’m calling

egz.df_energy['Main (kW)'].resample('15 min').asfreq()

so that the intervals between values are proportionate (otherwise missing values will cause calibration issues with the model’s timeline). I haven’t forgotten that I’m calling dropna() before this on df_energy. I’m dropping the null values (which are not all at 15-minute intervals), then reintroducing the null spaces where appropriate.

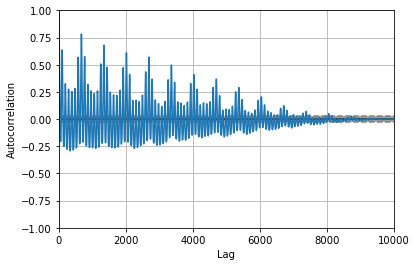

Here’s the autocorrelation plot for part of the data. The initial oscillation shows significance up to lag 30 (which is 8 hours of time).

Truncating the start of the sample

Right now my data starts in the middle of a day. I want to have nice windows that line up on the hour, so I’ll cut off the days that are incomplete as follows:

data.groupby(data.index.date).filter(lambda x: x.size==96)

There should be 96 15-minute intervals in a complete day. Note that this is not going to exclude days with missing values since I filled those spots with null placeholders.

Now my data starts at midnight on 08/05/15.

Splitting it into bins

Last time I made my bins from a rolling window, but that takes a lot of processing power when iterating over a lot of data. Also it’s unecessary for my training since I will only be predicting at the same intervals as my bin sizes (i.e. there’s no need to train the model how to make a forecast in the middle of an hour).

The grouping can be done with some nifty Python code:

groups = np.array(list(zip(*[iter(data)]*4)))

Read this for a breakdown of how the zip(*[iter(data)]*n) step works. It’s pretty clever.

On second thought I’m going to need to use sliding windows anyways (to get the selections from these hourly groupings). Luckily there’s a much more efficient way to do it in Numpy as described here. It gets into some hiden functions that access NumPy’s underlying C code. That post in particular provides a function for getting rolling windows with a desired window and step size, so I can set my step size to be 4 for an hour. That means I can replicate the behavior of the above code with

strided_app(data.values, 4, 4)